THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS. [Aug. 26, 1848.]

THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS. [Aug. 26, 1848.]

(By our Special Correspondent.)

THURLES.

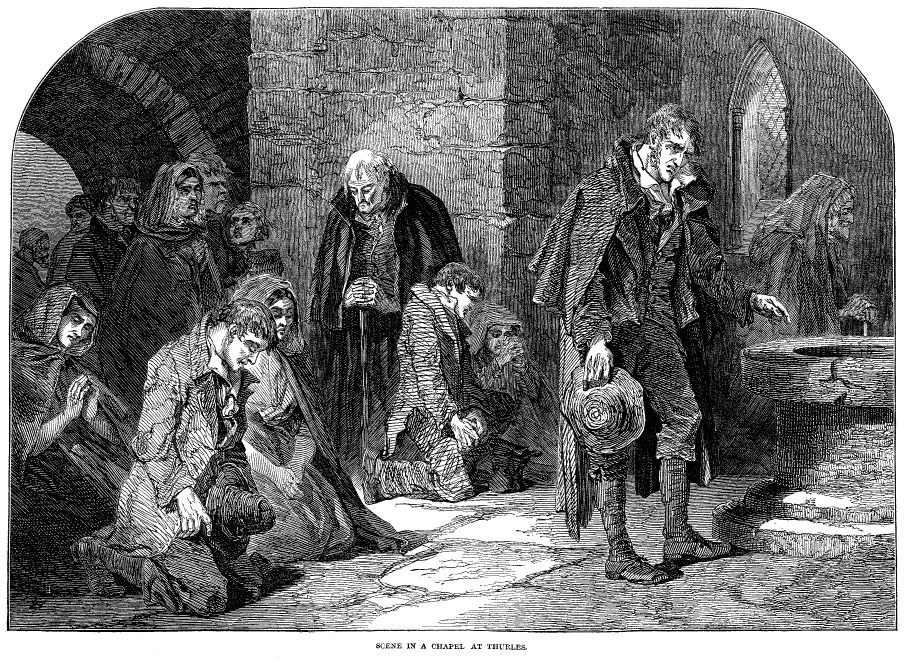

WERE it not the crowds of country-people who come into town to chapel, to market, and to hear the news, and the soldiers who fill the shops where whisky and porter, potatoes, eggs, salt, calico, linen, black-puddings, buttons, thread, and meal are sold, and the officers and “heaps” of gentlemen who puzzle the waiters and one another at the head hotel by ringing all the bells at once, as already told– there would be no sign of insurrection in Thurles. There is the fullness of the streets with country people, curious to ascertain what the military are doing; there are the detective police, curious to find out the business which brings any new-comer to Thurles, and who take round-about ways to satisfy their curiosity. There is the same philosophic amusement for those who are not otherwise too busy, of watching and studying the detectives. A visit to the Catholic chapel, where hundreds of the country people– the men in their dark blue or brown overcoats, with capes behind; the women in their blue hooded cloaks: all of them in good condition as to clothes; hardly a ragged coat, or cloak, or stocking to be seen– a visit to the chapel, where some hundreds are always, in the early part of the day, on their knees, is about all which the weather permits us to do (see Engraving); or we may follow some of them to the Court-house to hear their application for a license to keep fire-arms, and listen to the discussion as to their being or not being believed to be loyal subjects. Or we may linger under cover of the half-built railway station, and se the half-filled railway trains pass from Dublin to Limerick down, and from Limerick to Dublin up– three of them per day each way; and though the railway, by its easy gradients through a hundred miles of level country, with no tunnels, or viaducts, or deep cuttings, such as we see on almost every line in England, must have been cheaply constructed, we cannot help a mental calculation as to the small traffic and a small dividend.

But those are not subjects for a special reporter. The question of questions is, not what are the detectives doing to arrest the remainder of the insurgent leaders, or what is the light brigade of Major-General M’Donald doing to help them, but how is Ireland to be saved from an annual potato rot, and the famine which that and a poor system of agriculture leaves her a prey to, which, being the question, leads me again to Lord Clarendon’s practical instructors.

But those are not subjects for a special reporter. The question of questions is, not what are the detectives doing to arrest the remainder of the insurgent leaders, or what is the light brigade of Major-General M’Donald doing to help them, but how is Ireland to be saved from an annual potato rot, and the famine which that and a poor system of agriculture leaves her a prey to, which, being the question, leads me again to Lord Clarendon’s practical instructors.

Let us follow some of them.

To the neighbourhood of Macroom, in the county of Cork, Mr. John Hinds was sent. A reference to the evidence taken by the Commission which inquired into the occupation of land in 1844, under the able Presidency of the Earl of Devon, shows us that up to that year the custom of farming in the Macroom district was deplorably wasteful. When I visited the district during the famine months of the spring of 1847 I found all useful farm work abandoned, and the entire population working on the roads for the relief out of the ten millions which was voted for the purpose by Parliament. Not a perch of ground on the ordinary farms was broken with a spade or plough at the end of March. And, had the relief in food only allowed, it is a moral certainty that not a spadeful of soil would have been turned up, a grain of seed sown, or a plant planted in that district, as in others, except by a few of the gentlemen cultivators.

Being at last forced upon their own resources in 1847, the Macroom tenantry were probably more eager, in 1848, to listen to Lord Clarendon’s instructors than otherwise they might have been. Mr. Hinds says he first called upon the High Sheriff, the Hon. Mr. White, who received him favourably, and gave orders that his tenantry should be collected to listen to him, which was done. The instructor then travelled through the wild tract about the lakes which are the sources of the river Lee, which runs to Cork, and forms its harbour, a tract, though wild, thickly peopled. Everywhere he went the poor farmers crowded around him with the greatest anxiety. But alas! It was not an instructor to teach them how to till the land that they wanted; they looked for some one coming to till it for them– to find seed, pay for labour, and give them the crops. Mr. Hinds says they followed him over the whole country, from farm to farm. He pointed out to them as he went along, the defects of their old customs, and the advantages of the system which he recommended. He accompanied Mr. Coppinger, a poor-law guardian, over a large tract of country, near Mushera mountain; but he says it would be difficult to make anything of the poor creatures whom he met swarming there. “But, strange to say,” he adds, “some large farmers and gentry told me that it was now impossible to get farming labourers to work either by task or day upon the land, so completely are they demoralized and upset by the new system of labour that has been introduced among them (by the relief works). Instead of working at their own lands at home, or hiring themselves out as daily labourers, worthy of their hire, they now prefer working on the roads, like convicts in a penal colony; and I find groups of them in all parts of the county breaking stones for one pound of meal a day, hardly enough to support them, and their farms lying idle and neglected. If half the labour that is now spent on breaking stones could find its way back into the fields, and be employed in digging and deepening them, the country would soon feel the benefit of it, and the labouring population gradually come back to habits of industry and labour. As it is, the present system, if persevered in, must end in certain ruin.”

To this I would add, by way of suggestion, that if one pound of meal per day keeps these people upon the roads to break stones, a higher rate of wages than is usually offered to them by those who hire labour in that district might draw them from the roads and the pound of meal. It will hardly be credited that the “large farmers and gentry” spoken of by Mr. hinds offer labourers threepence and fourpence per day, without other allowance. The facts are simply these. The poor-law allowance is the very least which medical experience orders for the bare sustenance of life. Those who seek to hire labour offer less than the poor-law allowance, and the necessities of the wretched creatures decide in favour of the poor-law and the roads. The lowest-priced labour, like other low-priced commodities, is not always the cheapest. One of the most eminent political economists in England, Mr. Morton, of Whitefield, Gloucestershire, found that he could get any number of men to work for him for nine shillings a week on going to that farm. He preferred to give them twelve shillings a week, and has continued to do so. He has had better workmen, and better work, and cheaper labour for his twelve shillings, than those farmers who continue to pay nine shillings.

The half of nine shillings per week would be wages such as were never heard of about Macroom. If the half, instead of the fourth or the fifth of nine shillings per week, was offered for farm labour, the miserable men of Macroom would go to the farmer who offered it, and leave the roads and the one pound of meal a day.

But it is not so certain that those who have their five, ten, or fifteen acres of their own farm would leave the pound of meal to cultivate for themselves. If they borrow money at Macroom to buy seed or obtain food while the crop is growing, they must have two or three names to a bill, and pay 20, 30, or 40 per cent. for six months. So bad is their security deemed to be, that even that interest, nor any other interest that they may promise (they will promise anything), can obtain loans for them since the prevalence of the potato rot; consequently their land lies untilled. It is beyond the power of human knowledge to devise a plan by which these people are to be made men of substance, unless the plan of Lord Clarendon, of teaching them how to make their land fertile and their crops profitable, be followed out, in conjunction with such aid in seed and implements as other funds may for a time assist them in procuring. The Society of Friends in England have, through their agents in Ireland, distributed seed and implements over a great extent of country during the last two years.

Mr. Hinds found that the gentry did not attend his meetings, nor give him much of their countenance at Macroom. He determined, therefore, to go among the poor people on their own farms. The Rev. Mr. Burton, parish priest of Ballyvourney, secured him a good meeting in his parish. “We adjourned,” he says, “to the open air, and it was with difficulty I could make myself heard by the numbers who crowded round me for information. Only for the assistance of the clergy of all persuasions, I would not be able to struggle on at all in these vast tracts; but indeed they are doing their duty, and the people are everywhere beginning to feel the benefit of it.”

Then again he says: “I held meetings in Muskerry, which were well attended by the farmers; but, somehow or other, the gentry held back; and more is the pity, for all along the valley of the Lee the country is beautiful, the land fine, the people quiet and industrious. What they principally want, is instruction and co-operation from their superiors of wealth and resources.”

It is satisfactory to know, however, that the gentry became more favourable to the industrial mission as the season advanced.

Mr. Matthew Grace, who was sent as instructor to the Dingle district in Kerry, says the Rev. Owen M’Carthy, parish priest of Ballyheigne, “offered every assistance in his power to bring me in contact with the poor wretched inhabitants. He hopes to be able to get them some seeds, and that I will be able to instruct them in cultivating them.” Under the date of May 6th, he gives the following deplorable picture:– “The Reverend Mr. O’Sullivan, P.P. of Kilgobin, accompanied me over a large tract of poor desolate country, where I met several families digging their stubble land of last year and preparing for potatoes. The great difficulty here, as elsewhere, is the want of seeds. Mr. O’Sullivan told me he had known some of these poor people sell their beds, and carry them away privately by night from shame, in order to procure the seeds– and those who could not do so have only to let their land lie idle and to die themselves alongside it. Mr. O’Sullivan has himself prepared four acres of turnips, in the hope that the people will follow his example; but it is vain to expect anything from such broken down and dejected poor creatures as these.”

Mr. Matthew Grace, who was sent as instructor to the Dingle district in Kerry, says the Rev. Owen M’Carthy, parish priest of Ballyheigne, “offered every assistance in his power to bring me in contact with the poor wretched inhabitants. He hopes to be able to get them some seeds, and that I will be able to instruct them in cultivating them.” Under the date of May 6th, he gives the following deplorable picture:– “The Reverend Mr. O’Sullivan, P.P. of Kilgobin, accompanied me over a large tract of poor desolate country, where I met several families digging their stubble land of last year and preparing for potatoes. The great difficulty here, as elsewhere, is the want of seeds. Mr. O’Sullivan told me he had known some of these poor people sell their beds, and carry them away privately by night from shame, in order to procure the seeds– and those who could not do so have only to let their land lie idle and to die themselves alongside it. Mr. O’Sullivan has himself prepared four acres of turnips, in the hope that the people will follow his example; but it is vain to expect anything from such broken down and dejected poor creatures as these.”

On visiting Dingle a second time, Mr. Grace saw the good results of his first visit manifest. Land was prepared for green crops. The Rector introduced him to his congregation, to teach them how to dispose of the seeds sent them by the Society of Friends. At Castleisland he says his meetings were well attended by the clergy, and gentry, and the pauper tenantry. A committee was formed to get seeds and implements proper for the poor farmers. “Unless something effective to be done in this respect,” he says, “it is quite useless to be trying to get the poor creatures to alter their system, or to improve it, by bare advice or instruction.”

Mr. George Jordan, who was sent to the Swineford district, in the western county of Mayo, found it useless to instruct them while the wretched occupiers of the soil had not an ounce of seed nor any means of obtaining it, “unless it dropped down from heaven.” Small tracts on husbandry send to the instructors for distribution were everywhere eagerly sought for.

Mr. Thomas Wynne Boggs, who was sent to what he truly calls the splendid county of Roscommon, says:– “With the assistance of the clergy, I have been endeavouring to ascertain the quantity of tillage land in this splendid county of Roscommon, and we think it is about five acres tilled for forty-five acres untilled and lying idle. The great part of these rich and beautiful plains is covered with weeds and rushes. The people are wandering about, seeking for foreign food for breaking stones; their families starving; and that beautiful land, that ought to support them all and as many more, is lying idle like themselves and useless” (as grazing meadows).

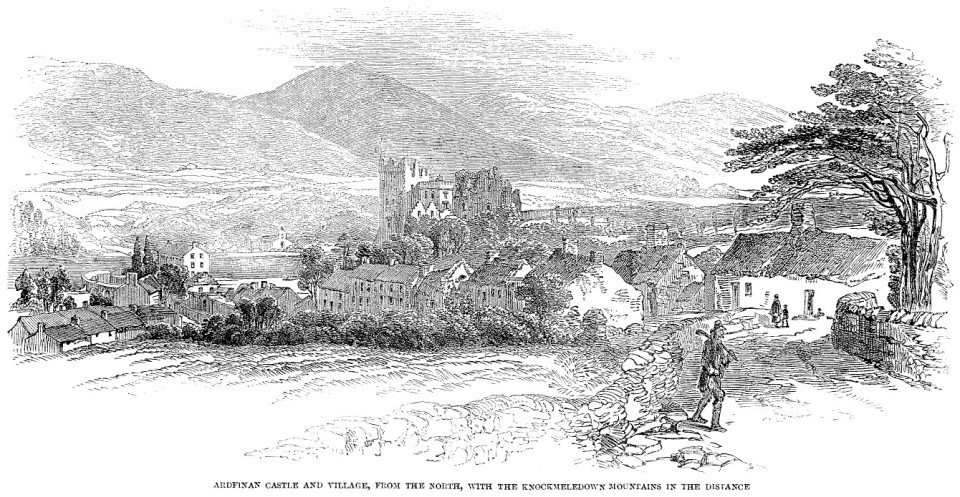

Since coming to the county of Tipperary, I have visited and observed some of the good effects following the instructions of Mr. Samuel Shouldice, who was appointed to the district of Ardfinan. Mr. Prendergast, Secretary to the Farming Society, guided him through the district about Market-hill. The farmers had sown their wheat crops, but in a defective way, great waste being caused by the numerous furrows and small narrow ridges. Mr. Prendergast pressed strongly on his tenants the necessity of adopting the instructor’s advice; and to enforce it by example he gave directions to his steward in their presence to follow his instructions, and to lay down the land strictly in accordance with them.

Mr. Samuel Barton, of Rochestown, took the instructor among his tenants, and provided some of them with seeds and implements, who seemed inclined to follow the instructions. He called on Mr. O’Connor, the parish priest of Ardfinan, and found him with five ploughs at work, preparing to sow potatoes alone. The value of a more varied system of cultivation was explained, so that if one crop failed others might succeed, and the Reverend gentleman, in the kindest manner, immediately placed his whole field, ploughs, manure, and seeds at the instructor’s disposal, to treat it as he thought proper. This act of confidence on his part had the best effect towards enlisting the feelings of the farmers, and inducing them to follow his example.

This was with the Catholic priest. Immediately after, the Protestant rector of the parish, the Rev. Mr. Madden sent for the instructor, and asked him to lay out his farm for him, which was done.

The competition for land– there being no other scope for industry– leads the people to give such large sums of money for the good-will or possession to outgoing tenants, as leave them destitute of capital to cultivate the land when they obtain it.

I shall not occupy space by alluding to more of the districts to which the instructors were sent. Their reports are all interesting. By a misfortune, not new to Ireland, the public press has not thought projects so simple, practicable, and really effective, worthy of its support– so I am informed on high authority. I have, therefore, been the more particular in making special inquiries for myself, and in bringing those beneficial services to Ireland fairly before the public.

The districts to which the instructors were sent are twenty-nine in number. To sixteen of them they were provided free of expense to the localities; to the remainder the localities contributed half the expenses. The payments were latterly £14 per fortnight to each instructor, the districts over which they travelled being extensive. The Lord-Lieutenant began the fund by a subscription of £50, and afterwards obtained £1000 from another source in England. The whole sum expended was £2433. Owing to the insurrectionary movements, all the instructors have been called in. If funds can be provided, it is intended they shall be sent out again in October, to direct the people during the winter and spring.

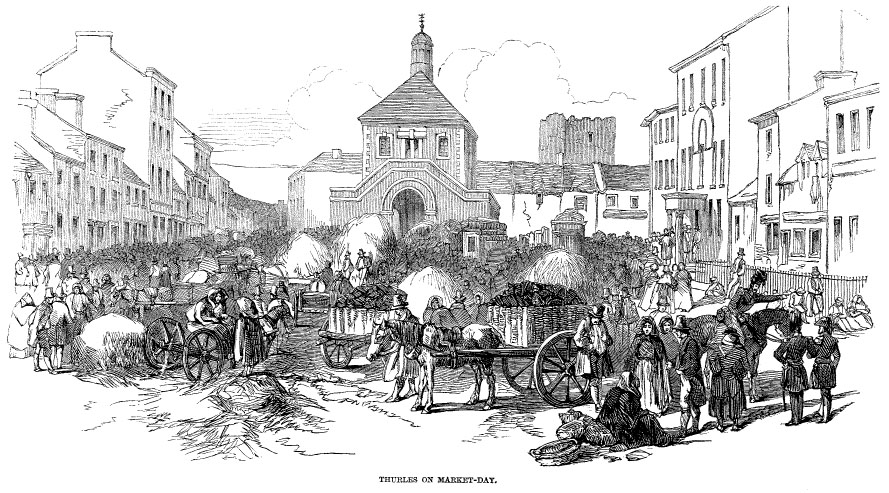

The weather continues wet, and every heart seems sinking at the unhappy prospect for the harvest. There have only been three entire dry days in the last fortnight; still most of the corn is safe, though it will not be so fine in quality, if the weather should brighten up. The peasantry come here early in the morning with buttermilk, potatoes, and scanty gatherings of greens, to sell, and linger in the market-place over their small sales all day; but the greater number who come seem to have nothing in hand of business kind.

We can hardly get them into conversation on the most ordinary topics: they think every stranger is a detective policeman. Even though innocent of insurrectionary sympathies, they fear an accusation. To a man standing near the railway I put some questions a little time ago about the crops, and the localities over which he had travelled. He trembled when I spoke, and became so tremulous that he could scarcely answer me. Sorry to see his uneasiness at being addressed by a stranger in such a perilous time, I left him, that he might be at ease, so far as I was concerned.

THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS. [Sept. 2, 1848.]

WE returned to the town of Thurles, in Tipperary, after accompanying the train which brought the prisoners to Dublin; but finding nothing occur to detain us at Thurles, which, for three weeks following the insurrectionary affray near Ballingarry, had been the locality of chiefest interest to the military, the police, and the reporters, we set our faces westward, and occasionally southward, on a tour through Tipperary county. It is about seventy miles long from north to south, and about forty miles broad from east to west, and comprises an area of 1659 square miles. Its surface in acres measures 1,061,731. Of those acres 843,887 are stated to be “arable” (that is cultivated– though in many respects badly cultivated), while 178,183 are wholly uncultivated, 23,779 are covered with plantations, 2359 form the sites of towns, and 13,523 are under water.

It is generally level or gently undulating, except on its borders, where southward we see the Galtees, the Knockmeledown ranges, and the Slievenamon solitary mountain; and in the east, where we see the Slieve Ardagh hills; and the west, where a group rises with the Keeper, shutting out the setting sun. The fame of Tipperary for agrarian outrages every ear has heard. The beauty of its surface no tongue can sufficiently declare. There is no English county that resembles it. Its wheat, its orchards, its high hedgerows, luxuriant and flowery in their wildness, you may see equalled in Kent; but Kent is without the mountains and the music of the rivers of Tipperary. On the other hand, weeds attempt to grow in the farm fields of Kent, as they do here; but they do not choke up the wheat and overcome its growth, and keep the potatoes often undermost, as they do here. Wages sufficient to induce men and women to work are paid in Kent; not so in Tipperary. Nothing is so continually manifest to the observer here, as the want of labour in the fields, and the number of people everywhere without employment, and declaring that nobody will employ them, not even at sixpence per day.

It is generally level or gently undulating, except on its borders, where southward we see the Galtees, the Knockmeledown ranges, and the Slievenamon solitary mountain; and in the east, where we see the Slieve Ardagh hills; and the west, where a group rises with the Keeper, shutting out the setting sun. The fame of Tipperary for agrarian outrages every ear has heard. The beauty of its surface no tongue can sufficiently declare. There is no English county that resembles it. Its wheat, its orchards, its high hedgerows, luxuriant and flowery in their wildness, you may see equalled in Kent; but Kent is without the mountains and the music of the rivers of Tipperary. On the other hand, weeds attempt to grow in the farm fields of Kent, as they do here; but they do not choke up the wheat and overcome its growth, and keep the potatoes often undermost, as they do here. Wages sufficient to induce men and women to work are paid in Kent; not so in Tipperary. Nothing is so continually manifest to the observer here, as the want of labour in the fields, and the number of people everywhere without employment, and declaring that nobody will employ them, not even at sixpence per day.

The population of the county was, at the taking of the last census, 435,553. There were 34,100 farms of more than one acre each (the average seems to run between 15 and 30 acres). The principal towns are Clonmel, with a population of 13,000; Nenagh, 8648; Carrick-on-Suir, 11,049; Thurles, 7523; Cashel, 7036; Roscrea, 5275; Fethard, 3915; Cahir, 3668; Templemore, 3683; Clogheen, 2049; and Tipperary, from whence the county takes its name, 7370.

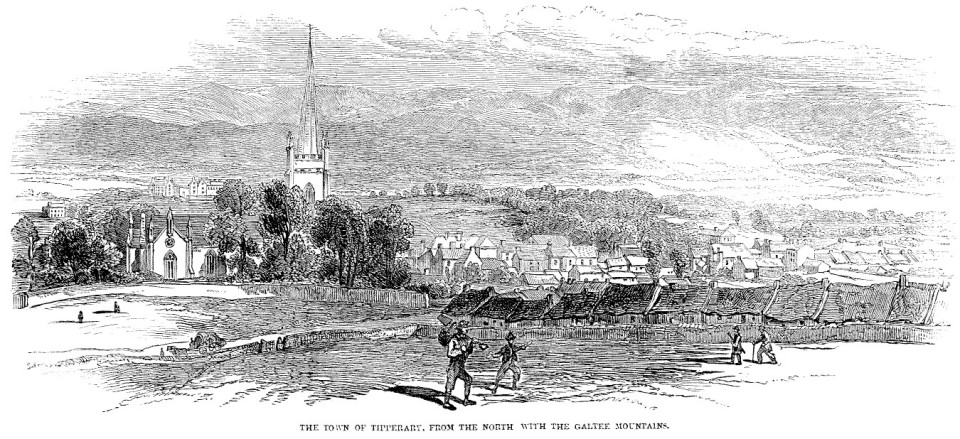

Tipperary town stands near the centre of the most fertile district of that fertile shire. It consists of one long main street running along an acclivity with a southern aspect, with lanes and other streets extending on each side. Viewed from a grassy eminence on the north side, we have before us the parish church; a row of mean cot houses, poorly thatched, inhabited by people poorly clothed, and complaining that they have no work to do; while, beyond the town, we have a view of the Workhouse and the Fever hospital, and another building, occupied at present as a barrack. Behind these rises a ridge of hills, the property chiefly of Augustus Stafford, Esq., M.P. (better known as Stafford O’Brien– having but recently obtained the Royal license to change his name); and behind that ridge of hills rise the Galtee Mountains– the vale of Aherle intervening. Viewed from the south, near the Workhouse, we have the unfinished railway station immediately before us, and the town, beautifully chequered with gardens and trees, rising beyond; those gardens, when we approach them and look over the walls, are so completely overgrown with thistles, docks, and luxuriant foulness, that you cannot tell nor even guess at the nature of the crop that may have been sown– whether potatoes, turnips, or cabbages. Outside the walls, by the pathway sides, and at every street corner, men, women, and children, of all ages and sizes, are gathering around strangers to beg; and to every question of “Why are you begging and not working?” the reply is “There is no work to do.”

Tipperary town stands near the centre of the most fertile district of that fertile shire. It consists of one long main street running along an acclivity with a southern aspect, with lanes and other streets extending on each side. Viewed from a grassy eminence on the north side, we have before us the parish church; a row of mean cot houses, poorly thatched, inhabited by people poorly clothed, and complaining that they have no work to do; while, beyond the town, we have a view of the Workhouse and the Fever hospital, and another building, occupied at present as a barrack. Behind these rises a ridge of hills, the property chiefly of Augustus Stafford, Esq., M.P. (better known as Stafford O’Brien– having but recently obtained the Royal license to change his name); and behind that ridge of hills rise the Galtee Mountains– the vale of Aherle intervening. Viewed from the south, near the Workhouse, we have the unfinished railway station immediately before us, and the town, beautifully chequered with gardens and trees, rising beyond; those gardens, when we approach them and look over the walls, are so completely overgrown with thistles, docks, and luxuriant foulness, that you cannot tell nor even guess at the nature of the crop that may have been sown– whether potatoes, turnips, or cabbages. Outside the walls, by the pathway sides, and at every street corner, men, women, and children, of all ages and sizes, are gathering around strangers to beg; and to every question of “Why are you begging and not working?” the reply is “There is no work to do.”

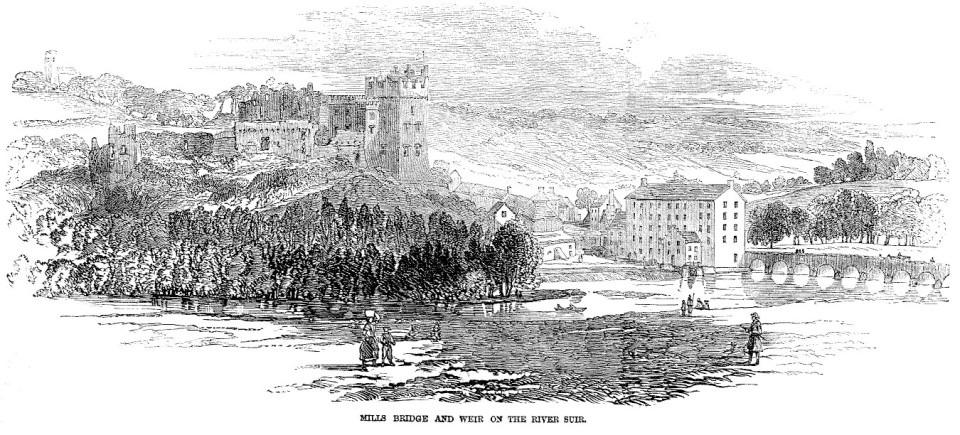

From Tipperary we travelled to Cahir, eleven miles. This town occupies a situation of singular beauty on both banks of the Suir river. It is chiefly the property of the Earl of Glengall. The well-cultivated fields, rich in their crops of grain, now ripe, and in process of being harvested, prove that some causes have been at work to improve this district. We obtained access to the tower of the Bridewell, from whence a good view of the town and surrounding country is obtained. From a point on the river side, below the ancient castle and bridge, we took another view. The large flour mills, one of which is beside the bridge, are objects of industrial interest, which the traveller finds occurring more frequently on the river Suir than on any other river in the south of Ireland.